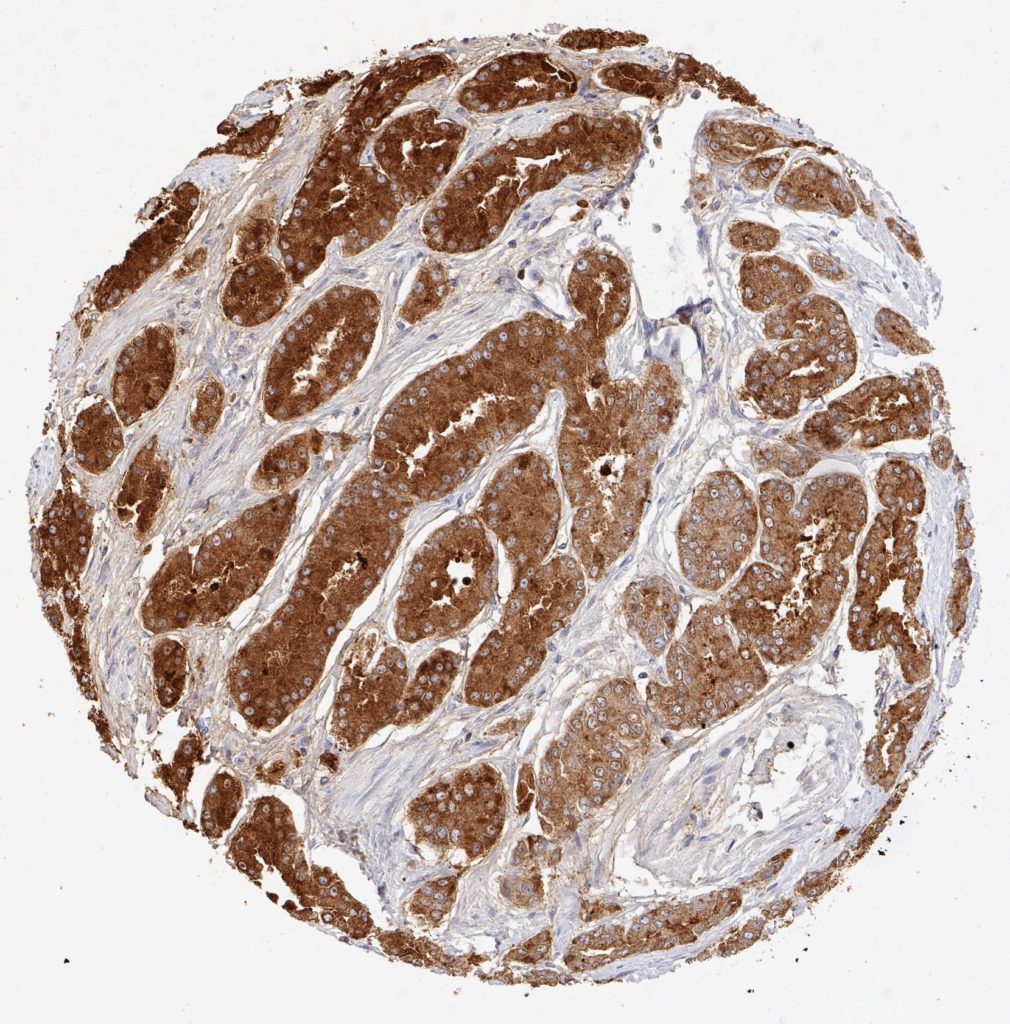

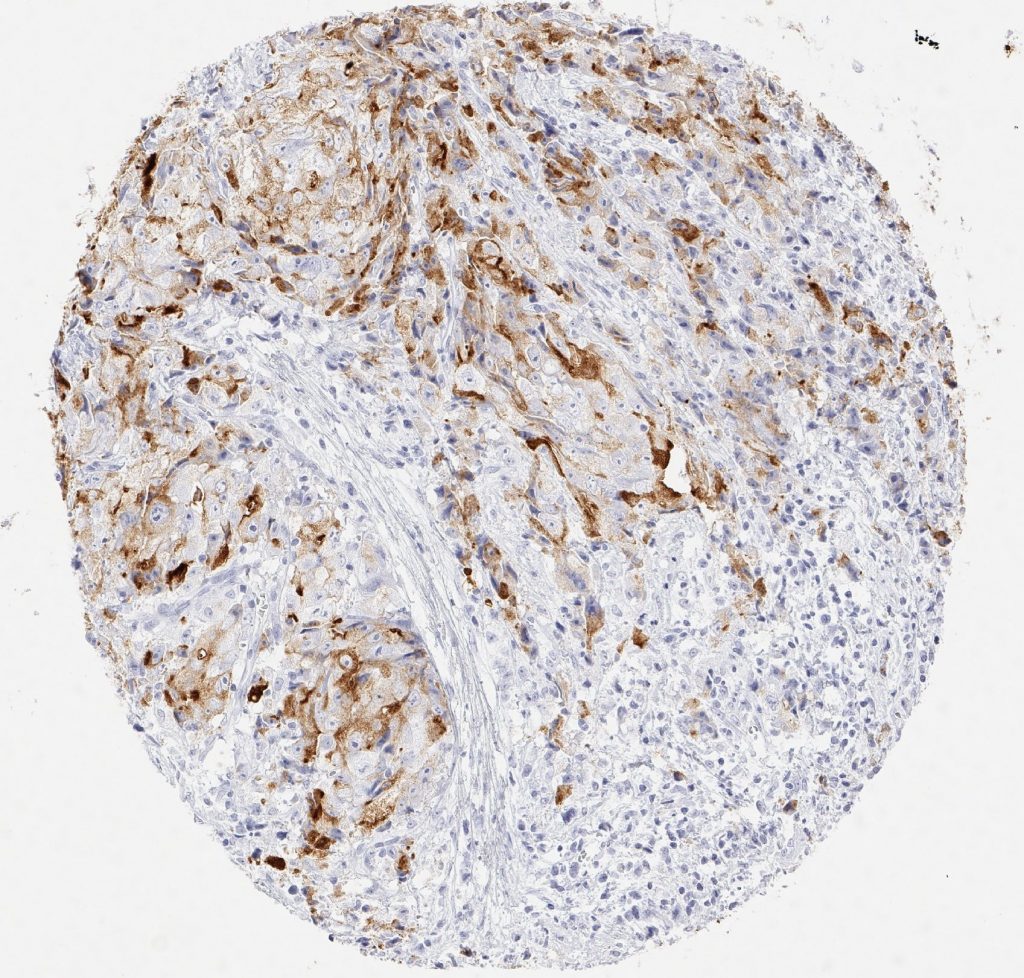

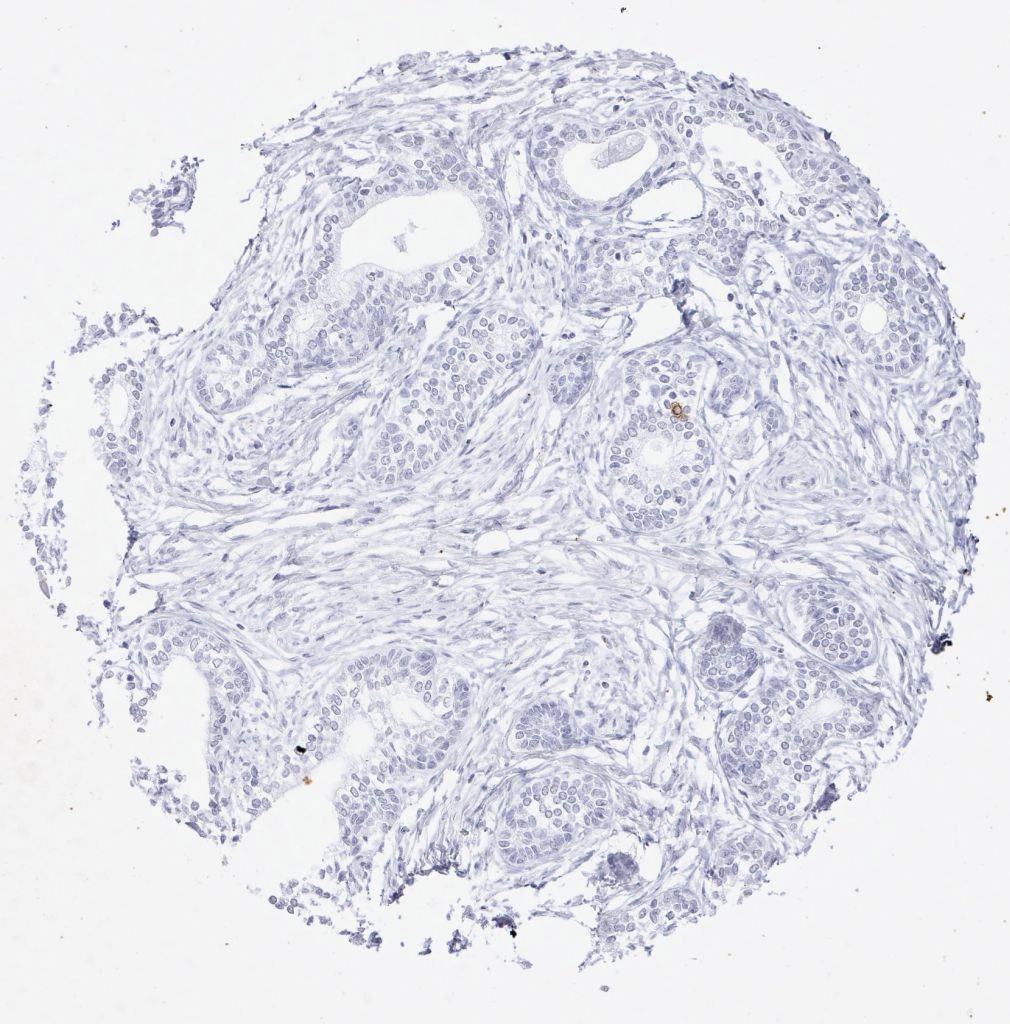

Der Anti-PSA (Prostataspezifisches Antigen) Antikörper Klon HAM 18 hebt sich von den mehr als 2.000 kommerziell erhältlichen PSA-Antikörpern durch seine dokumentierte hohe Spezifität und Sensitivität für die Erkennung von Prostatakrebs deutlich ab. Obwohl PSA ausschließlich in Prostataepithelzellen exprimiert wird, wurde in Studien mit verschiedenen anderen PSA-Antikörpern PSA-Expression bei 9% bis 60% der Brustkrebserkrankungen(1-8), bei 55% der malignen Melanome (7), bei 3%-9% der männlichen Brustkrebserkrankungen (8,9), 3 von 3 azinösen Pankreaskarzinomen (10) und bei verschiedenen Speicheldrüsenkarzinomen (wie 6 von 11 pleomorphen Adenomen, 1 von 6 Mukoepidermoidkarzinomen und 1 von 2 nicht näher spezifizierten Adenokarzinomen) (11-13) beschrieben. In mehreren Fallberichten wurde PSA-Expression auch in mindestens 4 Fällen von paraurethralem Adenokarzinom (14-18) und in einem Harnblasenkarzinom (19) nachgewiesen. Darüber hinaus wurde PSA-Expression in normalen Speicheldrüsen, 60% der Speicheldrüsenadenome und in normalem Bauchspeichelepithel beobachtet. (12) Unter Verwendung des Anti-PSA Antikörpers Klon HAM18 wurde in keinem dieser normalen und neoplastischen Gewebe PSA-Positivität beobachtet.

Die Validierung des Anti-PSA Antikörpers Klon HAM18 auf mehr als 20.000 Tumorgeweben, unter Verwendung des von Oncodianova empfohlenen Protokolls, bei einer Antikörperverdünnung von 1:800 ermöglichte eine genaue Dokumentation der Sensitivität und Spezifität des Antikörpers.

Wichtigste Kennzahlen zur Leistungsfähigkeit von HAM18:

Sensitivität

| Prostatakrebs Teilmenge | Analysierte Proben (n) | PSA positiv (n) | Sensitivität bei 1:800 (1:100) Verdünnung |

| Gleason 3+3=6 | 2.439 | 2.437 | 99,92% |

| Gleason 3+4=7 | 7.470 | 7.461 | 99,87% |

| Gleason 4+3=7 | 2.213 | 2.205 | 99,64% |

| Gleason 8 | 112 | 111 | 99,15% |

| Gleason 9-10 | 628 | 618 | 98,41% |

| Rezidivierender Prostatakrebs nach Therapie (Gleason ≥8) | 392 | 387 | 99,72% |

| Kleinzelliges Karzinom der Prostata | 13 | 1 | 7,69% |

Spezifität

| Tumortyp | Analysierte Proben (n) | PSA positiv (n) | Spezifität bei 1:800 Verdünnung |

| Adenokarzinom, extraprostatisch | 877 | 1* | 99,89% |

| Plattenepithelkarzinom, extraprostatisch | 319 | 0 | 100% |

| Kleinzelliges Karzinom, extraprostatisch | 46 | 0 | 100% |

| Andere extraprostatische Karzinome | 1.603 | 0 | 100% |

| Alle extraprostatischen maligne Tumore | 2.845 | 1 | 99,96% |

*Eine schwache extraprostatische PSA-Positivität wurde bei 1 von 30 endometrioiden Ovalkarzinomen beobachtet

Zertifizierten und akkredetierten Pathologielaboren wird die Verwendung umfassend validierter Antikörper unbedingt empfohlen.

In folgenden Fällen ist die PSA (HAM18)-Immunhistochemie in der diagnostischen Routine besonders hilfreich:

- Karzinom unbekannter Herkunft: Nachweis oder Ausschluss eines Prostatakarzinoms.

- Muskelinvasiver Blasentumor männlicher Patienten ohne histologischen Nachweis einer urothelialen Vorläuferläsion: Ausschluss eines in die Harnblase einwachsenden Prostatakarzinoms.

- Fortgeschrittener hochgradiger Prostatakrebs mit relativ niedrigen Serumspiegeln von PSA: bei schlecht differenziertem Krebs deutet eine niedrige PSA-Expression im Tumorgewebe darauf hin, dass die PSA-Serumspiegel die Gesamttumormasse des Patienten unterbewerten könnten.

Referenzen

Originalreferenz Antikörperklon HAM18

Bonk S et al. Prognostic and diagnostic role of PSA immunohistochemistry: A tissue microarray study on 21,000 normal and cancerous tissues. Oncotarget 2019 (10): 5439-5453. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.27145

Weitere Referenzen

[1] Poh BH, Jayaram G, Sthaneshwar P, Yip CH: Prostate-specific antigen in breast disease. Malays J Pathol 2008, 30:43-51.

[2] Alanen KA, Kuopio T, Collan YU, Kronqvist P, Juntti L, Nevalainen TJ: Immunohistochemical labelling for prostate-specific antigen in breast carcinomas. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1999, 56:169-76.

[3] Heyl W, Wolff JM, Biesterfeld S, Schroder W, Zitzelsberger D, Jakse G, Rath W: Immunohistochemical analysis of prostate-specific antigen does not correlate to other prognostic factors in breast cancer. Anticancer Res 1999, 19:2563-5.

[4] Miller MK, Unger PD, Bleiweiss IJ: Immunohistochemical analysis of prostate specific antigen in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2001, 68:111-6.

[5] Ilvan S, Celik V, Cetinaslan I, Calay Z, Ferahman M: Immunohistochemical analysis of prostate-specific antigen in female breast cancer. J BUON 2004, 9:183-6.

[6] Narita D, Cimpean AM, Anghel A, Raica M: Prostate-specific antigen value as a marker in breast cancer. Neoplasma 2006, 53:161-7.

[7] Bodey B, Bodey B, Jr., Kaiser HE: Immunocytochemical detection of prostate specific antigen expression in human primary and metastatic melanomas. Anticancer Res 1997, 17:2343-6.

[8] Kraus TS, Cohen C, Siddiqui MT: Prostate-specific antigen and hormone receptor expression in male and female breast carcinoma. Diagn Pathol 2010, 5:63.

[9] Carder PJ, Speirs V, Ramsdale J, Lansdown MR: Expression of prostate specific antigen in male breast cancer. J Clin Pathol 2005, 58:69-71.

[10] Kuopio T, Ekfors TO, Nikkanen V, Nevalainen TJ: Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas. Report of three cases. APMIS 1995, 103:69-78.

[11] van Krieken JH: Prostate marker immunoreactivity in salivary gland neoplasms. A rare pitfall in immunohistochemistry. Am J Surg Pathol 1993, 17:410-4.

[12] Elgamal AA, Ectors NL, Sunardhi-Widyaputra S, Van Poppel HP, Van Damme BJ, Baert LV: Detection of prostate specific antigen in pancreas and salivary glands: a potential impact on prostate cancer overestimation. J Urol 1996, 156:464-8.

[13] James GK, Pudek M, Berean KW, Diamandis EP, Archibald BL: Salivary duct carcinoma secreting prostate-specific antigen. Am J Clin Pathol 1996, 106:242-7.

[14] Svanholm H, Andersen OP, Rohl H: Tumour of female paraurethral duct. Immunohistochemical similarity with prostatic carcinoma. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol 1987, 411:395-8.

[15] Spencer JR, Brodin AG, Ignatoff JM: Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra: evidence for origin within paraurethral ducts. J Urol 1990, 143:122-5.

[16] Zaviacic M, Sidlo J, Borovsky M: Prostate specific antigen and prostate specific acid phosphatase in adenocarcinoma of Skene’s paraurethral glands and ducts. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol 1993, 423:503-5.

[17] Ebisuno S, Miyai M, Nagareda T: Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the female urethra showing positive staining with antibodies to prostate-specific antigen and prostatic acid phosphatase. Urology 1995, 45:682-5.

[18] Sloboda J, Zaviacic M, Jakubovsky J, Hammar E, Johnsen J: Metastasizing adenocarcinoma of the female prostate (Skene’s paraurethral glands). Histological and immunohistochemical prostate markers studies and first ultrastructural observation. Pathol Res Pract 1998, 194:129-36.

[19] Grignon DJ, Ro JY, Ayala AG, Johnson DE, Ordonez NG: Primary adenocarcinoma of the urinary bladder. A clinicopathologic analysis of 72 cases. Cancer 1991, 67:2165-72.